be a witness

One of the best pieces of advice I ever received came from my graduate school advisor. She was teaching a seminar on Black popular culture and several first-year Black male students came to class every week ready for a fight. Now that I’ve taught at the college level for close to ten years, I realize those young men were probably trying to challenge my Black woman professor’s authority. She always let them have their say before showing them the error of their ways, but I remember walking out of the room one day when I’d had enough of their foolishness. Later she told me I needed to stay in the room. “Be a witness,” is what I remember her telling me. “And be strategic. You can’t reason with every idiot.”

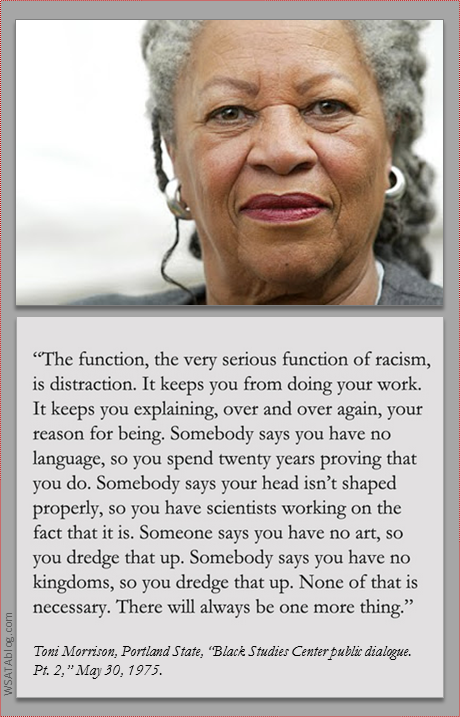

I’ve applied that advice over the years, learning when its best to hold my tongue and when I need to jump into the fray. I often think of Toni Morrison’s reminder that racism is a distraction, and so I try to focus on getting my work done instead of chastising white folks every time they mess up. When it comes to men of color and sexism, I generally reserve my remarks for my private conversations with other women of color; we know there are consequences that come with criticizing “our men” in public but when we’re together, we can talk about how it feels when white women editors, educators, and librarians knock us down in their haste to get next to the one straight male author of color in the room. In our own company, we’re able to safely discuss “misogynoir“—the very real discrimination we face as Black women writers in an industry that’s dominated by white women gatekeepers. When I wrote my critique of All American Boys last week, I focused on what was missing from the book: the agency and voices of young Black women. I thought about that provocative video project “Every Single Word,” where you only hear the lines spoken by people of color in major motion pictures. If we did something similar for All American Boys, what would we hear from girls of color on the topic of police brutality? Not much. I emailed Jason Reynolds when the post went up, and yesterday he took the time to write this response:

I’ve applied that advice over the years, learning when its best to hold my tongue and when I need to jump into the fray. I often think of Toni Morrison’s reminder that racism is a distraction, and so I try to focus on getting my work done instead of chastising white folks every time they mess up. When it comes to men of color and sexism, I generally reserve my remarks for my private conversations with other women of color; we know there are consequences that come with criticizing “our men” in public but when we’re together, we can talk about how it feels when white women editors, educators, and librarians knock us down in their haste to get next to the one straight male author of color in the room. In our own company, we’re able to safely discuss “misogynoir“—the very real discrimination we face as Black women writers in an industry that’s dominated by white women gatekeepers. When I wrote my critique of All American Boys last week, I focused on what was missing from the book: the agency and voices of young Black women. I thought about that provocative video project “Every Single Word,” where you only hear the lines spoken by people of color in major motion pictures. If we did something similar for All American Boys, what would we hear from girls of color on the topic of police brutality? Not much. I emailed Jason Reynolds when the post went up, and yesterday he took the time to write this response:

Zetta, thank you for this post. As one of the writers of All American Boys, I don’t necessarily feel any need to offer a rebuttal. I have no reason to be defensive. The points you raise are spot on, and they are, in fact, things I’d thought about in the process of making this book. I even had a hard time with the title for this very reason. My hope was that Tiffany, who worked closely with Jill, would sing out more prominently as part of the planning of the protest, but while focusing on the story of Rashad and approaching it from his first person narrative, it didn’t come across as such. And for that, I’m accountable. I own that. I felt similarly about Berry. *You* see her as a young woman who is doing what her boyfriend tells her, and doesn’t know about her little brother’s experience’s with the cops. *I* saw her as a powerful character, smarter than everyone else in the story, working hard to make change in the community. I saw her as a blazer. As someone whose “role” was at the *front* of the line — the only singular voice heard at the protest. She was the leader. But we were in Rashad’s head, in his family, in his vacuum, so all the information is being disseminated through his closest of kin, his brother. But maybe Rashad should’ve had a sister. Reading your post makes it clear that Berry doesn’t come across as I’d hoped. And that’s frustrating. The hard part about writing a book like this (for me) was knowing that there was no way I was going to hit all the marks. And admittedly, I didn’t. But it wasn’t a blind, ignorant scribble (not that you said it was.) I recognize fully how important it is to do away with the erasure of black girls and women, and I truly appreciate the call-out. And you have my word, I’ll continue to try to do better.

All the love.

People on Facebook and Twitter are praising our civil, reasoned exchange, and I understand why. Too often when an author gets called out, s/he responds with defensive vitriol. It’s clear from his response that Jason had a different narrative unfolding in his head, to which I would say: “If you need a Black feminist beta reader, let me know.” Because whenever a problematic book comes out, it points to a failure of process. Writing is a solitary activity, but publishing a book is not. It would have been great if the editor of this novel thought about the exclusion of Black girls. It would have meant a lot to me if some reviewers gave the book the praise it deserves but also pointed out this particular limitation. The fact that neither of those things happened confirms for me that a lot of people in the kid lit community aren’t really thinking about Black girls. I don’t generally review books but I published my critique on my blog because I was trying to be strategic. I’ve only met Jason once, but he seemed like an open-minded person and the comment he left on my blog proves that to be true. I also heard he has a ten-book deal, which means he’ll have plenty of opportunities to write (better) Black female characters in the future. Will reviewers and librarians and editors educate themselves about intersectionality and misogynoir? I doubt it. And that puts the onus on the writer—WE have to work harder because we can’t rely on others in the publishing process to get it right. No writer is perfect—I make mistakes all the time. But I care about Black youth and I know Jason does, too. And that’s why we have to help and look out for one another.

This would make a great panel, don’t you think?

Older Post ❱❰ Newer Post

7 Comments